36 ins wide, 21 ins deep and 39 ins high

For questions regarding viewing, shipping, and anything else,

contact us at: [email protected]

Provenance

Probably made for the Norris family of Oxfordshire

By descent to Colonel Henry Crawley Norris (1841-1914) who had houses at Swalcliffe Park near Banbury and Trinity Gardens in Folkestone

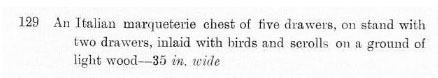

Sold by Col Norris’ executors at Christie’s on the 4th of May 1916, lot 129

Bought at the sale by Moss Harris for £8 8 shillings

Bought by Sir William Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme and situated in his palatial Hampstead mansion The Hill

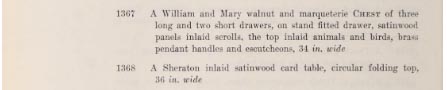

Offered for sale by Lever’s executors in a single owner sale from The Hill conducted by Knight, Frank and Rutley on the 19th-27th of October 1925, lot 1367, where unsold (see notes in the section on Viscount Leverhulme in the main text)

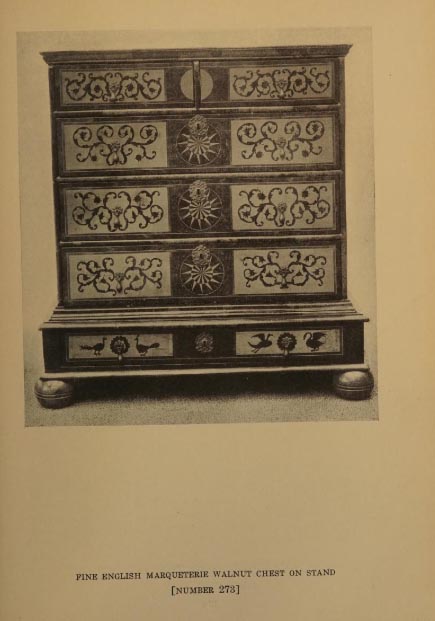

Taken to America with the bulk of Lever’s furniture and offered again at the Anderson Galleries in New York, 9th-13th of February 1926 where sold, lot 273, for $550 (illustrated in the catalogue)

The private collection of Matthew Allen Swift of West Hartford, Connecticut

Sold at Sotheby’s New York, 18th of October 2006, lot 168, for $63,000 where the piece was described in the catalogue introduction as the jewel in Mr Swift’s collection ‘one of the more fascinating pieces being the William III inlaid chest of drawers which was formerly in the collection of Viscount Leverhulme’

A private collection New York

Literature

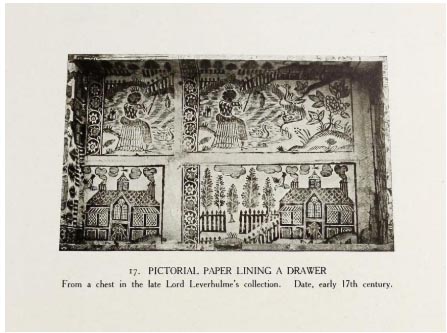

Brenda Greysmith,Wallpaper, 1976, pp.24-25 (the lining paper from our chest discussed and the V&A comparative illustrated)

Alan Sugden and John Edmundson, A History of English Wallpaper 1509-1914, 1925, p.20 and fig. 17 (the paper from one of the drawers in our piece illustrated and discussed)

Comparative Literature

Charles Oman and Jean Hamilton, Wallpapers: An International History and Illustrated Survey from the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1982, p. 98, no. 29 (the V&A comparative drawer lining paper illustrated and discussed)

Percy MacQuoid A History of English Furniture: The Age of Walnut, 1905, p.120 figs. 254-255 to comparable chests on stands of similar form but lacking the inlaid bird decoration.

This chest is both highly decorative and of great academic interest. Conceived as a chest on low stand, it rests on bun feet. The stand section consists of one long and narrow drawer set between two half round mouldings to top and bottom. The drawer front is inlaid with decorative roundels that mimic the shape of the handle plates utilised on the drawer and with charmingly naïve depictions of birds, seemingly swans to the right and a peacock and peahen to the left. Above the stand is a series of three long and two short drawers. All of the drawers have inlaid panels of rosewood scrollwork on the aforementioned satinwood or pale wood ground and the three long drawers also have parquetry sunburst panels inlaid to their centres, adorned with substantial and beautifully cast brass escutcheon plates. The top of the chest is inlaid with a geometric strapwork-type design with wide borders of burr yew and crossbanded panels of the pale wood. Each of these panels are then inlaid with birds or animals in rosewood. Top left and right are the lion and unicorn, symbolising the kingdoms of England and Scotland respectively and bottom left and right appear to be a male pheasant and potentially a female pheasant or even, as suggested by some of the past auction cataloguing, a goose. The central panel depicts two birds, one with wings spread, the other wings closed, and a barking dog.

Intriguingly, this chest retains its original block printed drawer lining papers which are incredibly rare survivors. A piece in the V&A retains extremely similar paper linings and the lining of our piece and the V&A example have both been published in specialist literature on wallpaper.

The Symbolic Importance of the Inlaid Creatures

In 17th century England, such inlaid animals as described above were highly unlikely to have been purely decorative. The original owner of this piece would almost certainly have selected these creatures for their symbolism as well as their visual appeal. It is interesting to note that of the various branches of the Norris family which were still in existence in 1905 when Fairbairn’s Book of Crests was published, one had a crest depicting a raven with wings elevated, potentially the large bird in the centre of the top, one a falcon, potentially the smaller bird although it should also have endorsed wings, and one had a (seated and collared) talbot hound. Although somewhat unlikely, it is just possible that the top of the piece may therefore be seen as some sort of playful heraldic reference to the various branches of the Norris line.

According to the American College of Heraldry, here are the various symbolic attributes of the creatures inlaid on this chest.

Peacock: beauty, power and knowledge

Swan: poetic harmony and learning, or lover thereof; light, love, grace, sincerity, perfection

Pheasant: person of many resources

Talbot (or any other dog): courage, vigilance and loyalty

When one looks at the needlework pictures produced in this period, for example, symbolism is rife in the depiction of figures and animals and it is highly likely that this piece was intended to be viewed in the same way.

Comparative Pieces

There are very few pieces of furniture that bear precise comparison to the present piece but two chests on stands are illustrated by Percy MacQuoid in his Age of Walnut, figs.254 and 255 (see below). Both of these pieces have been converted to bracket feet but the scroll work inlaid on the drawer fronts is comparable to the present piece in feeling even though it is generally busier in design on these two examples.

The Provenance of the Piece

We know for certain that the chest was owned by Colonel Henry Crawley Norris (1841-1914) and was in either his Oxfordshire home Swalcliffe Park or his house in Trinity Gardens in Folkestone until consigned to Christie’s by his executors in 1916. Norris’ name does not appear in the usual places one would expect to encounter it were he to have been one of the great early 20th century collectors and, looking at the other lots sold at Christie’s in the same sale, it seems highly likely that most of the pieces sold were acquired by family descent. A lacquer chest was described as having belonged to Admiral Nelson’s father and then come in to the Norris family via a marriage in Suffolk. This suggests that the family looked after their furniture and didn’t need to acquire antiques in the 19th and 20th centuries.

In The Story of Swalcliffe, Dorothy G. M. Davison dedicates a large amount of chapter VII in her book to the life of Col. Norris. The section below is quoted directly.

“In 1890 Major Henry Crawley Norris, his wife Mary and their two sons Harry and Jack came to live at Swalcliffe. Their daughter Dorothy had married and was living in Kent. Major H. C. Norris sold his property at Chacombe after the death of his father and he was ready to settle down at Swalcliffe. He was born in 1841 at Wroxton where his parents had their first home and where all the children were born. He had a happy childhood at Swalcliffe from where he went off to school at the age of seven. When he was nearly seventeen, consternation came to the family. He announced his intention of being a soldier and of his wish to go to India, there being the chance of some of the fighting at the end of the Indian Mutiny and of some sport in the jungle. Such an idea was unknown to the family, no one before had thought such a thing. But his father, Henry Norris, agreed and Harry went to Sandhurst first and then to India in 1858. Colonel North of Wroxton Abbey gave him his sword and Canon Payne, Vicar of Swalcliffe, gave him his bible. He went off in high spirits. He wrote long letters home, and he kept a diary during his time in India. In 1861, when he had been away for three years, he came home. There was rejoicing at Swalcliffe. The church bells rang, horses were taken out from the carriage and he was pulled in by willing arms. There was dancing on the higher lawn and a feasting afterwards for the village. In 1867 he married and brought Mary, his bride, to Swalcliffe. She was the daughter of Sir William Bovill, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. Her charm was appreciated and she received a warm welcome into the family. Two or three years later Captain H. C. Norris retired from the army and from his regiment the 8th Hussars and he and his wife lived at Holton near Oxford. Their eldest son, Henry Everard Du Cane Norris was born 1869 to the great satisfaction of the family. The baby was christened at Swalcliffe and was given a silver knife, fork and spoon in a case, by the people of the village. In 1875 Captain Norris began to build the house at Chacombe which had been his grandfather’s estate and which was made over to him by his father. It took two years to build the house which was of solid rough stone with mullioned windows. The best landscape gardener of the day was engaged to lay out the garden. During the two years while the house was building, Captain Norris was Aide-de-Camp to the Duke of Marlborough, Viceroy of Ireland, spending much time at Dublin Castle and the Vice Regal Lodge. In 1877 he retired into his house at Chacombe with his wife and his three children. Chacombe, several hundred years before, had had a celebrated bell foundry and the six bells of Swalcliffe church and of other parish churches in the neighbourhood. So in 1890 another generation occupied Swalcliffe. The house was adapted to modern ideas. The saloon became the drawing room, resplendent with rose coloured brocade curtains. Furniture was re-covered, china was unearthed from protecting cupboards and the room lost its stiffness. The Chippendale sofas showed the beauty of their corners. Plants and flowers in mahogany and brass-bound tubs etc. were put in unexpected places giving colour and scent to the room and adding to the medley of pink and rose, of brown and green already there. The door to the morning room was locked up and the opening through the thick walls became a cupboard on the farther side. The morning room became a smoking room and the old study was neglected. A door was made in the wall of the dining room leading to the billiard room, but except for small alterations, the house remained the same as before. The verandah was taken down and the house assumed a more important air, it looked taller and more solid. Much of the Victorian furniture disappeared and the older things of the 18th Century were repolished and took on new life. Harry Norris loved the place and was pleased to be back there. Many guests came and went and he and his beautiful wife Mary, paid constant visits to friends and neighbours in the country round. He was a first rate shot and a good raconteur of amusing stories. He was full of fire and life and had an original way of looking at things. The Warwickshire hounds often met at Swalcliffe Park where Colonel and Mrs Norris loved to entertain them. The best bunches of grapes were produced for the Hunt breakfast, when the dining room was full of red-coated, white leathered, top-booted men, and ladies in their smart, well-fitting habits and shining top hats. They would come through to the drawing room, where a roaring fire would be burning at the end of the room. The flowers on these occasions were a feature, the hot house producing magnificent cyclamens, the blossoms of which formed a complete mass of white or colour, excluding the green of the leaves. Chrysanthemums also were magnificent and took many a prize and different flower shows and the conservatory was full of colour. Colonel H. C. Norris was fond of hunting and of seeing his friends, but though he was full of energy, he was not a strong man. He liked to see things wells carried out. Uniforms with his yeomanry and dress clothes of the Warwickshire Hunt were very important to him and his black knee-breeches and silk stockings and the black velvet collar to the red tail-coat were immaculate when he attended Hunt Balls and other functions. He hunted about two days a week and kept two or three hunters which he shared with his sons.”

Again it is interesting to note that Mrs Davison’s account implies that the family’s 18th century (and earlier) furniture had been in their possession all along but had been neglected until Henry took over the running of the estate, having been replaced by modern Victorian pieces.

A wonderful English delftware flower holder, the oldest dated example known, in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge also came from the Norris collection and the same sale at Christie’s as our chest. It is further evidence of the importance of the family’s possessions.

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/71777

The Importance of the Printed Drawer Lining Papers

What is particularly wonderful about this piece is that it retains the original woodblock printed drawer linings, probably made from what was originally intended to be panoramic wallpaper. A closely related piece of this paper is in the V&A, having been discovered inside a triangular oak box in the Croft Lyons Bequest in the Department of Furniture and Woodwork, W.51-1926. Sensing the importance of the survival of this piece, the museum decided to remove it from the box and conserve it as a paper sheet in the prints and drawings department instead in 1968, new object number E.405-1968

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O70392/wallpaper-unknown/

The museum’s object history description for the paper is quoted below.

“This appears to be a contemporary reworking of a lining paper found in a drawer of a chest belonging to Lord Leverhulme (SE, pl 17; Greysmith, pl 13). In the background, the palings and trees are practically identical to those shown in another scene, from Colonial Williamsburg, USA, which was a companion piece to the hunting scene from Clandon Park (no 30). This companion piece shows a chinoiserie figure walking over a hill. There is obviously a common source, perhaps a painted cloth hanging, for all 3 scenes, which may have been intended to be shown in conjunction with one another, forming an early example of a panoramic paper.

Reproduced as pl.17 in A History of English Wallpaper, 1509-1914 , by A.V. Sugden and J.L. Edmundson, 1926.”

What makes the papers in our piece significantly more important than the example in the V&A, however, is the fact that the pieces are not only woodblock printed but retain their original period hand colouring, the V&A example being uncoloured.

The survival of this paper in our piece adds yet another layer to its fascinating history and importance as a piece of folk art as well as a wonderful piece of furniture.

Viscount Leverhulme (1851-1925)

Making his fortune through the soap empire that he centred at Port Sunlight near Liverpool, William Lever is a towering figure amongst the collectors and connoisseurs of the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Britain. He collected widely, forming astonishing collections of items as diverse as needlework pictures, tapestries, modern paintings, books, Wedgwood and Chinese porcelain but the mainstay of his collections was the furniture. Leverhulme acquired his pieces largely through a small circle of dealers, particularly D. L. Isaacs and his successor Moss Harris and Frank Partridge, at that stage in King Street, St James. Leverhulme’s appetite for fine furniture was virtually insatiable and despite owning the enormous Thornton Manor in Cheshire, Moor Park in Hertfordshire and his palatial Hampstead mansion known as The Hill, he was able to furnish each property with vast numbers of pieces. Leverhulme established a wonderful gallery and museum in his wife’s honour in Liverpool, the Lady Lever Art Gallery, which flourishes to this day and the ex-curator of furniture there, Dr. Lucy Wood, has written two important catalogues of the commodes and the upholstered seat furniture in that collection. In 1928, Percy MacQuoid, who had previously created the Adam room in the Lever Art Gallery for Leverhulme, published a three volume catalogue of the museum’s holdings at that point but there were several sales of his property after that point including a landmark sale at Sotheby’s in 2001 where exceptional prices were achieved. These later sales, however, pale in to insignificance compared to the prices achieved at the sales just after Leverhulme’s death in 1925 and 1926. It is probably because of the high reserves attached to certain lots in 1925 and the fact that, due to the immense size of the sales, there was something of a glut of exceptional furniture all released on to the market at one time, that many of Leverhulme’s most important pieces, including the present chest, did not sell when offered. These pieces were then taken to America and offered in an equally important sale at the Anderson Galleries in New York and there they found a very dedicated audience, American collectors at this stage beginning to establish their dominance in the market for English furniture. Our piece fetched $550 in this sale and has been in America, and the New York area, ever since.

Images

(The chest when offered at the Anderson Art Galleries sale in 1926)

(The description of the chest from the 1925 Knight, Frank and Rutley catalogue, proving that the piece was situated in The Hill and not Thornton Manor)

(The piece, erroneously catalogued as Italian, in the 1916 Christie’s sale of the Norris collection)

(The lining paper in one of the drawers illustrated in A History of English Wallpaper 1509-1914. The caption mistakenly describes the paper as early 17th century but the text makes it clear that it is late 17th century instead).

(The chest when offered at Sotheby’s New York in 2006 where it sold for $63,000)

Research and essay by Christopher Coles.